Newly proposed changes to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) may entice Canadians who are able to make outsized donations to be a little more charitable this year. But come 2024, charities fear the tax changes could dampen those gifts at a challenging time.

The AMT is a parallel income tax calculation that Ottawa initially put in place in 1986 to ensure higher-income earners cannot combine certain tax incentives to significantly reduce their tax bill. In the 2023 federal budget, Ottawa committed to tweaking the way the AMT is calculated. “It’s a follow up from the Liberal party’s campaign promise to make sure ‘everyone pays their fair share’,” says Phil Haines, Director, Tax Planning for BMO Private Wealth.

The change is not sitting well with high-income earners and charities because it could drastically reduce the tax incentives linked to the donation of securities to charity. In late September, Donald K. Johnson, a Director at the UHN Foundation who also serves on other charitable boards, penned an open letter to the Prime Minister, warning in bold letters that proposed changes “will discourage many potential large-scale donations, jeopardizing many charities’ operations.” The letter, which appeared in the print-edition of the Toronto Star on September 22 and signed by 30 other major Canadian charities, cautions that the change will disrupt an important source of income that has generated more than $1 billion in donations since 1997.

Proposed AMT changes

Amongst the proposed changes, the federal government plans to broaden the AMT base, increase the AMT rate to 20.5% from the current 15%, raise the basic exemption level to an estimated $173,000 (indexed to inflation) from a fixed $40,000, and further limit tax preference items (i.e., exemptions, deductions and credits, such as the donation tax credit) in calculating the AMT.

“One of the biggest impacts is expected to be on charitable giving, especially where individuals are donating shares of publicly-traded companies,” says John Waters, Vice President and Director of Tax Consulting Services at BMO Private Wealth. With Ottawa seemingly targeting donations, some higher-income Canadians may feel incentivized to donate more this year before the new rules become effective in January 2024.

Under the current rules, 100% of the donation tax credit will be applied under the AMT, but one of the proposed changes is to drop that down to 50%. At the same time, 30% (vs. 0% currently) of capital gains incurred when donating publicly-listed securities is proposed to be included in the AMT calculation in 2024.

Waters describes the changes as a double whammy for charitable high-income earners who donate securities. “You get the hit on the increased capital gains inclusion, and you get the hit on donations,” he says. “As a result, some who give to charity may pay a higher rate of taxation.”

While some of these philanthropists may have concerns, Haines is quick to caution against making any hasty changes to your gifting plans since the changes are not yet enacted and will only affect a small segment of the population. “The vast majority of people out there have nothing to worry about,” he explains. Thanks to the increase in the basic AMT exemption to $173,000 per individual, the new rules should mainly impact higher-income individuals. Middle-class income earners gifting generously to charities won’t trigger the AMT, says Haines.

Gifting securities under the new AMT

Still, for those who are impacted by the proposed change, the tax bill could be significant. Here is how the AMT might impact an individual realizing a large capital gain, perhaps on the sale of a business or property, who also makes a significant donation of publicly-traded securities to offset some of the tax resulting from that sale.

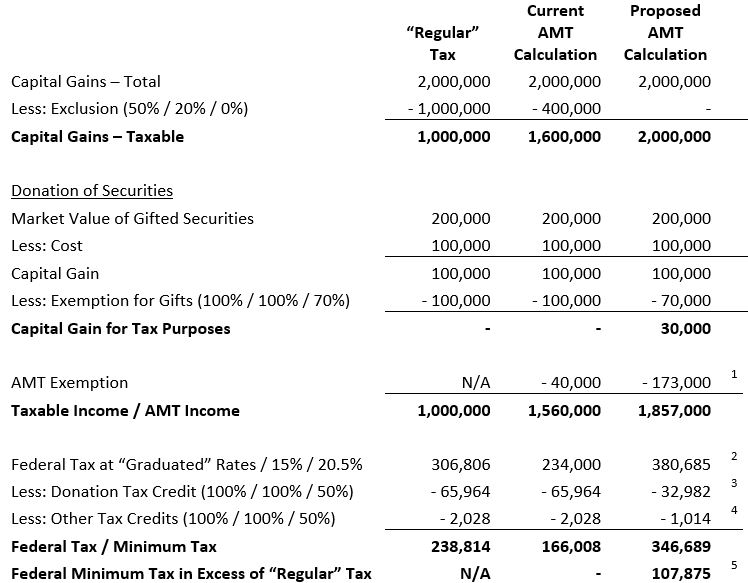

Scenario 1: Individual realizes $2,000,000 of capital gains and donates $200,000 of appreciated securities (with a $100,000 cost base)

1 The basic AMT exemption is proposed to increase from $40,000 in 2023 to the start of the second-highest federal tax bracket, which is expected to be approximately $173,000 in 2024.

2 Federal marginal tax rates and brackets for 2023 used for calculating “Regular” tax.

3 Federal donation tax credits are valued at 15% of the first $200 of gifts, and 33% of the remainder where taxable income exceeds the top marginal tax bracket. Note that annual donation claims are limited to 75% of net income (100% in the year of death).

4 Other tax credits include only the basic personal amount in this scenario.

5 Only the federal AMT is presented for illustration purposes. All provinces and territories impose a minimum tax and, in most provinces, the provincial AMT component is represented as a percentage of the federal AMT.

Under this scenario, the proposed changes to the AMT would result in over $100,000 in additional tax, whereas previously the AMT wouldn’t have resulted in any additional taxes in excess of the “regular” tax.

More modest income earners who make smaller donations of securities won’t face the same situation under the proposed AMT formula.

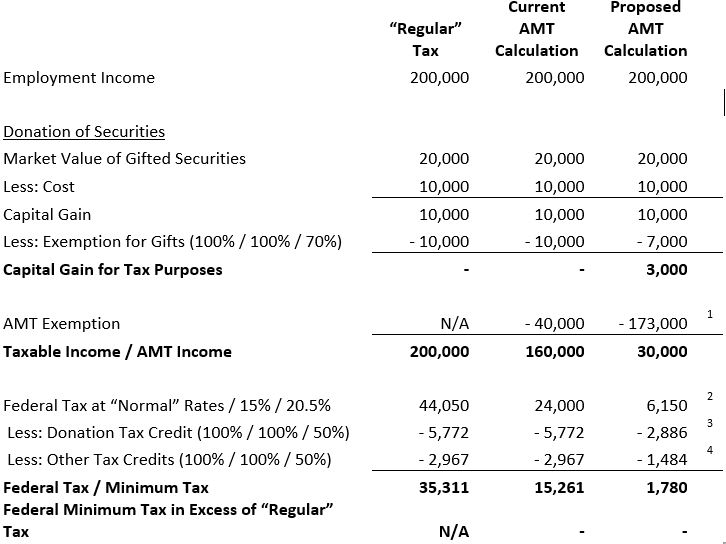

Scenario 2: Individual earning $200,000 of employment income and donates $20,000 of appreciated securities (with a $10,000 cost base)

1 The basic AMT exemption is proposed to increase from $40,000 in 2023 to the start of the second-highest federal tax bracket, which is expected to be approximately $173,000 in 2024.

2 Federal marginal tax rates and brackets for 2023 used for calculating “Regular” tax.

3 Federal donation tax credits are valued at 15% of the first $200 of gifts, and 29% of the remainder where taxable income does not exceed the top marginal tax bracket. Note that annual donation claims are limited to 75% of net income (100% in the year of death).

4 Other tax credits include only the basic personal amount, as well as CPP, EI and Canada employment amounts in this scenario.

These two scenarios underline the concern charities and high-income earners have about the proposed changes.

Other impacts of the proposed AMT changes

Business owners looking to exit their business or anyone selling a secondary piece of real estate, like a family cottage or an income property, may also want to pay close attention to the changes to the AMT. “Sometimes people will have a large income year for tax purposes, but they’re not necessarily a high-income earner in the conventional sense,” says Haines. “Now, anyone who’s going to be deriving a substantial proportion of their income in a particular year from capital gains could have this AMT exposure.”

Any high-income earners who are able to claim significant deductions or credits may also be exposed to the new AMT. This is especially true for Canadians who earn a substantial portion of their income from capital gains (as noted above) or dividends, since the dividend tax credit is removed from the AMT calculation, explains Waters.

Managing your tax bill

Although the AMT proposals have yet to be formally enacted, Waters says setting up a donor-advised fund this year to get ahead of the AMT changes could be a way for high-income earners to manage their taxes, especially if they haven’t decided how they want to gift their funds. Your BMO Private Wealth professional can help you set up a donor-advised fund as part of the BMO Charitable Giving Program to help you get an immediate income tax deduction in the year of the gift and enable you to distribute the funds for grant-making over an extended period of time.

A Charitable Gift Fund, or donor advised fund, is a turn-key solution to provide a way for you and your family to work together to enhance the giving experience. A donor advised fund provides you with a highly flexible and customizable philanthropic solution to leave a lasting impact on causes that matter to you and your family.

For those who are expecting a one-time increase in their income, which makes them potentially subject to the AMT, Haines offers a glimmer of hope. Those individuals may be able to get some or all of their AMT payments refunded over time, he explains, noting that they have seven years to recover the AMT that they pay in a particular year. It’s also worth noting that the AMT only applies to individuals and trusts and doesn’t apply to corporations or in the year of death, he adds.

“Obviously, people are still going to be philanthropic, independent of the tax benefits of doing so,” says Waters, but he feels it could discourage those who are tax-motivated in their giving. He expects most will still give, but it may be less – or more strategic – than what they would have given under the old rules.

If you have questions about how the AMT might affect you, be sure to talk with your tax advisor before making any changes to your giving strategy.