Estate planning requires special considerations for Indigenous people who are subject to the laws set out by the Indian Act1 (therein referred to as status “Indian”.2 ) and other relevant legislation.

If you are a registered Indigenous person under this legislation, it is essential that you find an estate planning lawyer with the expertise needed to ensure your estate plan complies with these complex and detailed rules. This article provides a brief overview of the relevant laws, particularly restrictions in transferring interests in reserve3 land on death.

Legislative framework

Typically, laws regulating estates and distributions on death, known as “succession laws”, are set out in provincial statutes. Succession laws typically regulate the validity of Wills, the scheme of distribution on intestacy,4 legal tests for capacity, and specific procedural matters regarding the distribution of estates. The Indian Act imposes a separate framework on the estates of Indigenous people who are registered under the legislation and are “ordinarily resident on reserve land”.

The Indian Act also deals generally with the management and transfer of “reserve” land, powers allocated to “Bands”,5 and the powers of the Minister of Indigenous Affairs.6 Other provincial laws continue to apply to reserve land.7

Jurisdiction of the Minister over the estates of registered Indigenous people

The Minister has wide powers to decide on matters regarding the estates of registered Indigenous people who are ordinarily resident on reserve land. This standard, of being “ordinarily resident”, is decided based on the facts of the individual’s “customary mode of life”. If you might be “ordinarily resident” on reserve land, you should be mindful of the areas in which the Minister might have discretionary power over your estate.

Some of these succession rules include choosing and appointing an executor or administrator to administer the estate, declaring the validity of, or voiding, documents purporting to be the Will of a registered Indigenous person, and directing the executor or administrator of the estate to comply with certain rules. This does not mean that a registered Indigenous person cannot direct most of their estate in their Will as they wish; it does, however, mean that additional complications arise in the administration of their estates as the Minister has unilateral jurisdiction over many issues that would otherwise be dealt with by a court. Restrictions do arise, however, in how interests in reserve land can be dealt with in an estate.

Jurisdiction of the Minister over the transfer of reserve land

Most critically for estate planning purposes is the jurisdiction of the Minister in regulating the transfer of reserve lands. While land outside a reserve is owned by the individual in whose name title is registered, land on a reserve is owned by the Crown for the benefit of the Band which resides on the land, with Certificates of Possession issued to members of the Band. The Minister approves the holder of every Certificate of Possession, and such rights can only be issued to members of the same Band.

Similar restrictions apply to Certificates of Occupation, which are issued by the Minister to those entitled to possession of reserve land by order of the Band, direction in a Will, or pursuant to the rules of intestacy. A Certificate of Occupation permits the holder to temporary Occupation while the Minister considers approval for the Certificate of Possession.

These possessory interests can be passed on in a Will, but only to members of the same Band and subject to the approval of the Minister. If you have either of these Certificates, or become entitled to them in the future, understanding these restrictions is critical in preparing your estate plan. Keep in mind that a person can only be a member of one Band, and you should be aware of the Band membership of your spouse or common-law partner, as well as your children, in planning the distribution of your estate.

Laws of intestacy applying to registered Indigenous people

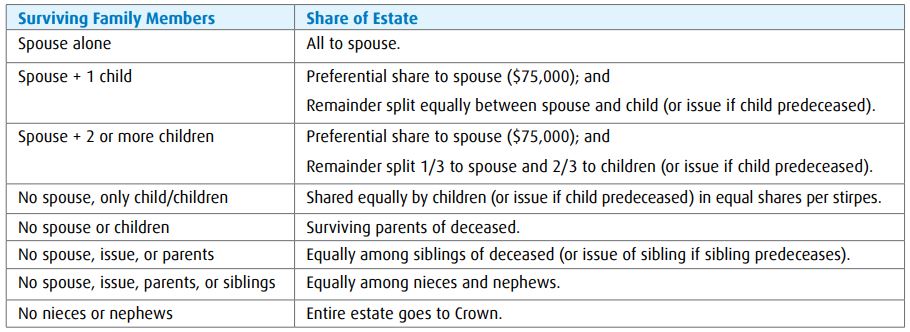

The laws of intestacy determine who is entitled to receive the estate of an individual who dies without a Will and are typically governed by provincial legislation dealing with succession laws. The estate of an intestate registered Indigenous person is, however, subject to a different scheme, that is set out in the Indian Act.8 These rules are very similar to the general intestacy rules of each province, with key differences in the amount to which the legally married spouse of the deceased is entitled, and the remoteness of the relatives which are entitled to a share of the deceased’s estate (particularly with respect to reserve land).

The following chart outlines the applicable rules of intestacy:

Please note: No interest in reserve land shall vest in relatives more remote than the siblings of the deceased, the implications of which is described in the next section.

Restrictions on transfers of reserve land

Transfers to remote relatives

If a relation of a deceased registered Indigenous person would be entitled to a share in the deceased’s estate pursuant to the rules of intestacy, the limitations on remoteness are relevant for interests in reserve land. Specifically, as noted above, as no interest in reserve land can vest in the deceased’s nieces and nephews, even if they are members of the same Band and reside on the same reserve, the deceased’s interest will instead revert to the Band.

Transfer to persons who are not Band members

If an individual who is not a member of the Band where the land is located obtains a Certificate of Possession or Certificate of Occupation to reserve land through the Will of a registered Indigenous person or pursuant to the laws of intestacy, that individual cannot obtain the possessory interest to that land. This means they cannot have the same rights to the property as an individual who is a Band member. They are, however, entitled to compensation for the value of the right to the land.

• The Superintendent of the Band may auction of the rights to a member of the Band, transferring the proceeds of sale to the beneficiary.

• If there are no purchasers, the rights to the land will revert to the Band. However, the Superintendent of the Band may pay compensation to the beneficiary out of the Band’s funds. The beneficiary will have no further claims to the land.

You should confirm if any of your proposed beneficiaries are members of your Band, if you are thinking about transferring rights to reserve land to them.

Matrimonial property rights

Different rules apply to spouses of deceased Band members when the spouse is not a member of the Band and the matrimonial home of the couple was located on the reserve. Typically, the family law rules in the province where the couple resides would dictate rights to matrimonial property, such as rights to the matrimonial home. However, the rights of registered Indigenous people are subject to a different scheme.

• Each Band is empowered to enact by-laws specific to the Band on certain matters,9 including the residence of Band members and other persons on the reserve,10 and providing for rights of spouses and common-law partners and children who reside with members of the Band on the reserve.11 If a deceased Band member has a non-Band member spouse surviving them, and the matrimonial home was located on the reserve, the Band’s by-laws regarding use, occupation, or possession of the property will apply.

• If there are no such by-laws enacted for the relevant Band, then rules that are set out in the Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act12 apply regarding the rights of the surviving spouse or common-law partner to the family home, including an automatic right to occupy the home for 180 days after the death and the right to apply for occupation beyond the 180-day period. The survivor may otherwise inherit from the deceased Band member under the terms of their Will or pursuant to the rules of intestacy, as noted above, unless the survivor applies for a division of matrimonial property.

These rules are complex, and a detailed understanding of these rules and how they would impact your estate plan is critical.

Seek advice

Keep in mind that the rules discussed in this article are those set out in Federal legislation. As noted, each Band may set out by-laws specific to them, or there might be Indigenous laws beyond the scope of the Canadian legal system which might inform the traditions and practices that govern the death of an Indigenous person.

If you qualify as, or have questions about an estate of, a registered Indigenous person, please contact your local Band for further guidance and for a copy of their relevant by-laws. It is critical that your estate planning lawyer has the expertise needed to plan within the limitations of these rules.

For more information, please speak with your BMO financial professional.

1 R.S.C. 1985, c. I-5, hereinafter referred to as “the Indian Act”. The Indian Estates Regulations, C.R.C. 1978, c. 954, are also relevant in these testamentary matters.

2 Defined generally at section 2 of the Act as a person who is entitled to be registered as an “Indian”. The criteria for registration as an “Indian” is set out in the lengthy sections 5 and 6 of the Indian Act.

3 The term “reserve” is defined at section 2 of the Indian Act to refer to land that has been set aside by the Crown for the benefit of a Band and, in limited situations, other designated lands.

4 Situations when an individual dies without a valid Will.

5 Also defined generally at section 2 of the Indian Act to refer to a group of individuals meeting the definition of “Indian” and for whose benefit reserve land has been set aside, for whose benefit the Crown holds money, or declared to be a Band by the Governor in Council.

6 Hereinafter referred to as the “Minister”.

7 Indian Act, section 88.

8 Set out at section 48 of the Indian Act.

9 Indian Act, section 81.

10 Indian Act, paragraph 81(1)(p.1).

11 Indian Act, paragraph 81(1)(p.2).

12 S.C. 2013, c. 20. This statute deals with rights arising in the family law context. See the Provisional Federal Rules as described in section 12, and section 34 for the rights to the matrimonial home on the death of a spouse or common-law partner.

Information contained in this publication is based on sources such as issuer reports, statistical services and industry communications, which we believe are reliable but are not represented as accurate or complete. Opinions expressed in this publication are current opinions only and are subject to change. BMO Private Wealth accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from any use of this commentary or its contents. The information, opinions, estimates, projections and other materials contained herein are not to be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation for or an offer to buy, any products or services referenced herein (including, without limitation, any commodities, securities or other financial instruments), nor shall such information, opinions, estimates, projections and other materials be considered as investment advice, tax advice, a recommendation to enter into any transaction or an assurance or guarantee as to the expected results of any transaction.

You should not act or rely on the information contained in this publication without seeking the advice of an appropriate professional advisor.

BMO Private Wealth is a brand name for a business group consisting of Bank of Montreal and certain of its affiliates in providing private wealth management products and services. Not all products and services are offered by all legal entities within BMO Private Wealth. Banking services are offered through Bank of Montreal. Investment management, wealth planning, tax planning and philanthropy planning services are offered through BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. and BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. Estate, trust, and custodial services are offered through BMO Trust Company. BMO Private Wealth legal entities do not offer tax advice. BMO Trust Company and BMO Bank of Montreal are Members of CDIC.

®Registered trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under license.